Diversity Committee Reports/Updates

February 2022

Presenting the 2021 Diversity Award Winner- Dr. Ruth Zúñiga

Jess Binkley, PsyD, OPA Diversity Committee

On December 6, the Diversity Committee hosted the 2021 Diversity Award Ceremony to honor Dr. Ruth Zúñiga. Many members of the OPA community were in attendance, in addition to over 30 colleagues and associates of Dr. Zúñiga’s from her community-based work. The OPA Diversity Award recognizes a licensed psychologist with a record of a strong and consistent commitment to diversity through their clinical work, research, teaching, advocacy, organizational policy, leadership, mentorship and/or community service. We define diversity in its broadest sense, including work with a wide range of minority populations, persistent efforts related to social justice, inclusion, and equity, as well as strengths in the domains of cultural awareness and competence.

Biography: Biography:

Dr. Ruth Zúñiga completed her doctorate at the University of Alaska, where she studied clinical and community psychology with a rural and indigenous emphasis. In her time at the University of Alaska, Dr. Zúñiga was involved in both research and clinical work focusing on health and wellness initiatives with the Alaska Native community and other marginalized groups. Dr. Zúñiga is currently an Associate Professor at Pacific University’s School of Graduate Psychology. Since 2013, she has been the Director of the Sabirudía program, which focuses on community-based service, outreach, and clinical work with the Latinx community.

Dr. Zúñiga is also the co-founder of a non-profit, Raices de Bienestar, which offers clinical services, consultation and education, and training focusing on culturally grounded mental health services with the Latinx community. Services at Raices de Bienestar are offered through a trauma-informed, culturally focused lens that honors the inherent wisdom and resilience of the Latinx community. Please see https://www.raicesdebienestar.org/ for more information.

In addition to her teaching, clinical, and consulting work, Dr. Zúñiga serves on multiple board of directors and advisory boards focusing on the Latinx community. She has given countless community presentations on the mental health needs and resiliencies of the Latinx community, and is the recipient of multiple grants focusing on supporting the Latinx community’s emotional health and wellness, including most recently during the Covid-19 pandemic. She is also an active collaborator with multiple community agencies including Elemento Latino, PCUN, Oregon Latinx Leadership Network, Trauma Informed Oregon, Providence Health and Services, Susan G. Komen of Oregon and SW Washington, and the Mexican Consulate.

On the whole, Dr. Zúñiga is an active leader and trusted member of the Latinx community in Oregon. She has a longstanding history of research, advocacy, and community-based service with the Latinx community, and is also trusted and looked to as a role model by her students and colleagues. Dr. Zúñiga has demonstrated a strong commitment to social justice, cultural awareness, and responsiveness throughout her clinical work and outreach, research, community service, and teaching. The Diversity Committee, and the broader Oregon Psychological Association, express our profound appreciation for Dr. Zúñiga and her work.

November 2021

Diversity Committee- 2021 Updated Mission Statement and Goals

In August 2021, our Diversity Committee met and made modifications to our mission statement and goals (see below). Our committee remains focused on outreach and involvement with the BIPOC community, and aims to develop sustainable advocacy and mentorship efforts. We welcome new members whose input and engagement can help shape the direction of the committee as we move toward our goals and strengthen our work with the community. The Diversity Committee meets 8-10 times per year, currently on Zoom. If you have any questions, or are interested in joining our committee, please email your CV and a letter of interest to Jessica Binkley, Psy.D. at [email protected].

2021 Mission Statement

The ultimate goal of the Diversity Committee is to support diverse psychologists in Oregon, as well as OPA and its leadership, reach the level where consideration of diversity issues is intuitive. It is essential in today’s society that issues of social justice and cultural humility be kept in the forefront of every psychologist’s mind and throughout all OPA activities.

2021 Goals

- Provide advocacy, support, and networking opportunities for students and psychologists who are of diverse backgrounds and/or who work with individuals of diverse backgrounds

- Foster awareness and knowledge about diversity, multicultural humility, and psychological practice

- Ensure that CE workshops reflect a commitment to integrate information about diversity into the education of psychologists, and remain particularly accessible to BIPOC students, psychologists, and community members

- Increase recruitment, retention, mentoring, and participation of diverse members within OPA

July 2021

Considerations When Providing Therapy to Asian American Clients

Valerie Yeo, PsyD, Oregon Psychological Association Diversity Committee

The past year has brought about renewed reminders about the violence and outsider status Asian Americans experience. Many politicians have repeatedly used racist rhetoric like “kung flu” and “China virus,” resulting in the rise of Sinophobia and other anti-Asian sentiments, including physical violence. According to the United States census, Asian Americans were the fastest growing racial or ethnic group in the United States between the years 2000 to 2019. There are more than 28 different groups within Asian Americans as a whole, each encompassing distinctive language, history, and cultural norms. Historically, Asian Americans have also suffered from discriminatory laws, including the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and the Page Act of 1875. While clearly not a monolithic group by any stretch, research shows that Asian Americans as the whole experience high incidences of mental illness and distress, substance abuse, and domestic violence. Yet, Asian Americans are also likely to underreport these occurrences and underuse mental health services. This is likely due to multiple factors, including mental health stigma, and lack of culturally congruent mental health services and culturally competent providers (Kwok, 2013). Many mental health providers consider learning about different cultures when engaging in the work of cultural competence. However, merely understanding a client’s culture is insufficient when conducting therapy with a client from a marginalized, or non-dominant, group. Doing so “reinforces the problematic assumption that the difficulty of culture is located in the client as other, rather than the cultural difference between the client and the provider” (p. 2). True cultural competence also requires self-awareness on the part of the therapist, which includes understanding one’s relationship to racism on personal, interpersonal, and institutional levels, as well as the role of privilege within the therapeutic relationship. Further, there has been limited research regarding the effectiveness of traditional psychotherapy for Asian American populations (Grey & Hall-Clark, 2015).

Thus, in the interest of cultural competence when working with Asian American clients, it is important for psychologists to foster awareness about phenomena impacting Asian Americans. It is likely that most have heard the term model minority myth. This myth has been a prevailing frame for how Asian Americans have been perceived by dominant American culture. The stereotype frames Asian Americans as a monolithic racial group who have achieved success via hard work—despite the fact that income inequality in the United States is greatest amongst Asian Americans. In fact, the gap in the standard of living between Asian and Asian Americans at the top and bottom of the income ladder has almost doubled between 1970 and 2016 (Pew Research Center, 2018). Yet, the model minority frame has been and continues to be used as a tool of white supremacy, by refuting evidence of systemic racism perpetuated by dominant culture toward other marginalized racial groups, most notably African Americans. The prevalence of this stereotype has been instrumental in advancing a so-called colorblind ideology, a counterproductive agenda that serves to obscure and increase racial inequity (Poon et al., 2016). Furthermore, this stereotype has also been shown to contribute to suicidality, lowered self-worth, and difficulty accessing help and resources when needed (Noh, 2018).

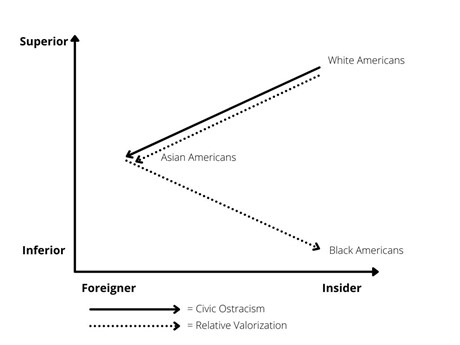

Additionally, the model minority myth situates Asian Americans in a racial bind between the white community and other Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) groups. This condition is demonstrated by the concept of racial triangulation, a sociopolitical theory created by Claire Jean Kim in 1999, arguing that Black, Asian, and white people occupy unique racial positions in society based on varying historical and cultural narratives. According to racial triangulation theory, Black Americans are seen by white culture as the most inferior of the races, and are positioned below Asian Americans, although Asians are still positioned below white Americans. Yet despite being seen as the most inferior, Black Americans are also perceived as less foreign than Asian Americans—Asians are portrayed as perpetual foreigners and ostracized from American society for being un-American. Kim called this process “civic ostracism,” and it allowed for the creation of the model minority myth as a means of putting down Black communities “relative valorization” (Kim, 1999, p. 109). Racial triangulation theory is depicted in the following graphic (adapted from Kim, 1999, p. 108).

Kim posited that Asian Americans are presented by the dominant culture as a standard of success, while simultaneously limited in their voice and minoritized. As a recent example, during the resurgence of Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020, Black Americans were accused of violence, radicalism, and dangerous political upheaval. In contrast, Asian Americans were praised for being passive, apolitical, and hardworking, even while violence toward Asian bodies sharply increased and Asian working-class residents and employees were quickly becoming displaced during the same period of time. By disregarding the lived experiences of one minoritized group in order to shame and discipline another minoritized group, white dominance was able to redirect scrutiny away from itself (Kim, 1999; Poon et al., 2016).

For any provider treating Asian American clients, it is important to keep these concepts in mind. In particular, clinicians who desire to continually move toward cultural humility can also help other members of our profession better understand the ways in which they might transform access and care in the field of psychology through sensitivity to these topics.

References

Grey, H., & Hall-Clark, B. N. (2015). Cultural considerations in Asian and Pacific Islander American mental health. Oxford University Press.

Kim, C. J. (1999). The racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Politics & Society, 27(1), 105–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329299027001005

Kwok, J. (2013). Factors that influence the diagnoses of Asian Americans in mental health: An exploration. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 49(4), 288–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12017

Noh, E. (2018). Terror as usual: The role of the model minority myth in Asian American women's suicidality. Women & Therapy, 41(3-4), 316–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2018.1430360

Pew Research Center. (2018, July 12). Income inequality in the U.S. is rising most rapidly among Asians. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/07/12/income-inequality-in-the-u-s-is-rising-most-rapidly-among-asians/

Poon, O., Squire, D., Kodama, C., Byrd, A., Chan, J., Manzano, L., Furr, S., & Bishundat, D. (2016). A critical review of the model minority myth in selected literature on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in higher education. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 469–502. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315612205

May 2021

Racial Battle Fatigue and Resilience within BIPOC Communities

Jessica L. Binkley, PsyD, OPA Diversity Committee

As Vice President Kamala Harris recently stated, racial injustice is a problem for every American (Harris, 2021). Although racism causes harm to all Americans, the impact of racism on Black, Indigenous and People of Color (hereafter referred to as BIPOC communities) has a unique and debilitating toll. In addition to the effects of colonization as well as historic oppression and discrimination, BIPOC communities are assaulted on a regular basis by news, images, and videos of murders and other horrors committed against their community members.

Both historic and daily experiences of racism shape the identities, activities, health, and psychological welfare of BIPOC communities, particularly in predominantly White spaces (e.g., schools, workplace; healthcare). Smith and colleagues (2007) coined the term racial battle fatigue to describe the physiological and emotional distress caused by both immediate and chronic experiences of microaggressions, environmental stress, and blocked opportunities experienced by BIPOC communities. Their original study focused on Black male college students, and the psychological as well as physiological stress responses Black men reported as a result of unrelenting anti-Black stereotyping, racial microaggressions, and increased surveillance both in public and in private settings on college campuses. These authors found that psychosocial stressors affecting BIPOC communities, and particularly Black men, not only cause psychological stress (e.g., disappointment, hopelessness, anger, intrusive thoughts and images), but also physiological stress (e.g., hypertension, insomnia, headaches, chronic illnesses), resulting in behavioral stress responses (e.g., stereotype threat, substance use, irritability, avoidance).

Similar to other trauma-related responses, Smith et al. (2007) conceptualized racial battle fatigue as a natural reaction to living and working in dangerous and distressing conditions. White communities in turn then may view BIPOC communities, particularly Black men, as argumentative, hypersensitive, and irritable when they protest (or even discuss) acts of discrimination and oppression, rather than viewing these expressions as natural responses to unrelenting trauma (Legha & Miranda, 2020). In addition, as a result of exerting continuous energy to cope with constant environmental stress, BIPOC communities have fewer and less readily available personal resources to direct toward individual and community activities and goals.

In a later study on racial battle fatigue, Smith and colleagues (2011) explored the cultural attitude of individualism. Individualism refers to the belief that the individual has control over both themselves and the environment; individualist attitudes de-center the impact of environmental and relationship factors on a person’s sense of self and instead focus on an individual’s ability to effect change on the world around them. These authors noted that people possessing an individualistic ideology may both excuse enactments of White privilege (e.g., through de-emphasizing the relational impact of the self on one’s community) while also placing blame on BIPOC populations for disparities in academic achievement, health, and socioeconomic outcomes. Because individualistic ideologies are privileged in dominant discourses, BIPOC communities may be at risk of internalizing attitudes of self-blame while also needing to work harder than their White counterparts to experience success in any domain. The psychological burden of navigating race-based stressors (e.g., identifying if, when, and how to respond to oppression; navigating hostile and physically dangerous environments) and institutional racism, all while navigating harmful internalized messages and dangerous environments, requires substantial resilience, which psychologists would do well to recognize.

In becoming better educated about racial battle fatigue, psychologists can contribute positively to strengthening an actively racist identity and clinical practice. Guideline 10 of the APA Multicultural Guidelines (APA, 2017) underscores the importance of taking a strengths-based approach, which acknowledges both trauma and resilience-related factors. More recently published guidelines for providing actively anti-racist mental health care (Cénat, 2020) also recommend conceptualizing experiences of racism and their impact on BIPOC mental health from the lens of intergenerational trauma, rather than as an expression of individual pathology. On the whole, recognizing and understanding racial battle fatigue with a trauma-informed and actively anti-racist lens may reduce harmful stereotyping while also highlighting the resilience of BIPOC communities.

References

American Psychological Association. (2017). Multicultural guidelines: An ecological approach to context,

identity, and intersectionality. http://www.apa.org/about/policy/multicultural-guidelines.pdf

Cénat, J. M. (2020). How to provide anti-racist mental health care. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(11), 929-931.

doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30309-6

Harris, K. J. (2021). Remarks by Vice President Harris on the verdict in the Derek Chauvin trial for the death

of George Floyd. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/04/21/remarks-by-vice-president-harris-on-the-verdict-in-the-derek-chauvin-trial-for-the-death-of-george-floyd/

Legha, R. K., & Miranda, J. (2020). An anti-racist approach to achieving mental health equity in clinical care.

Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 43, 451-469. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2020.05.002

Smith, W. A., Allen, W. R., & Danley, L. L. (2007). “Assume the position…you fit the description”:

Psychosocial experiences and racial battle fatigue among African American male college students.

American Behavioral Scientist, 51(4), 551-578. doi: 10.1177/0002764207307742

Smith, W. A., Hung, M., & Franklin, J. D. (2011). Racial battle fatigue and the miseducation of Black men:

Racial microaggressions, societal problems, and environmental stress.

The Journal of Negro Education, 80(1), 63-82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41341106

March 2021

Tactics for enhancing white allyship: Article review of Hardy’s (2016) PAST model

Jess Binkley, PsyD, OPA Diversity Committee

As a white woman, I have often observed myself engaging in behaviors inconsistent with my values and desire to be an antiracist ally. For example, I have monologued or over-focused about less privileged aspects of my identity, and/or become otherwise defensive during conversations in which I am invited to learn about the lived and painful experiences of people of color. As it is important to me to continue to advance my own antiracist identity and racial stamina, I have been curious about how to utilize aspects of what I have identified as a part of white culture (e.g., “doing” something, completing tasks) to grow. In reviewing some literature by authors of color within the fields of social justice and psychology, I came across a model describing specific tactics for enhancing conversations about race.

Dr. Kenneth Hardy (2016)’s Privilege and Subjugated Task (PAST) Model aims to support clinicians, coworkers, and the general public in defusing conflict and increasing engagement during conversations about race. Although the PAST model can be used when discussing other intersections of identity, Hardy emphasized the importance of maintaining focus on race whenever possible. In this regard, he noted that conversations about identity that initially center on race can be at increased risk of becoming sidetracked or deflected to other topics, often when a white person engages in monologue about their own marginalized identities (e.g., class, sexual orientation). Much akin to DiAngelo’s (2011)’s writings about white fragility, Hardy emphasized that white allies must build racial stamina and work to remain focused and emotionally regulated as they confront racial justice issues, including when exploring their own racial identity. He offered five tasks of the privileged party (white people) and five tasks of the subjugated or marginalized party (people of color) during conversations about race, as well as tactics to support antiracist approaches. I will focus in this article on tasks of the privileged party, in an effort to highlight how white allies may enhance their ability to address their own privilege and confront white supremacy in order to show up for people of color.

The first task of the privileged party is to be clear on the difference between intention and consequences, and to begin conversations by acknowledging the consequences of their actions. For example, rather than focusing on intention (e.g., “I didn’t mean to…”), Hardy (2016) recommends that white people first take responsibility for the impact of their actions on the other person and on the relationship. As reflected in Tactic #1, “Focus conversations on the consequences experienced by the subjugated person,” white allies must be able to refrain from highlighting their positive intentions and first offer acknowledgment and validation of the experiences of people of color (p. 128).

Hardy’s (2016) second task requires the privileged party to avoid overtly or covertly negating any disclosures or experiences shared by the marginalized party. He emphasized that white people often respond to experiences of white fragility by negating the experience of people of color through a variety of tactics, including challenges disguised as questions or advice (e.g., “Are you sure that (event, comment, interaction) was racist?” White people also have a tendency to fall silent or express misdirected empathy by attempting to equalize their experiences with people of color (e.g., “As a queer person, I understand what it’s like to be discriminated against”). The aforementioned behaviors have the effect of minimizing the lived experiences and feelings of people of color. Consistent with Tactic #1, Tactic #2 involves offering validation (rather than falling silent, overshadowing, or otherwise negating people of color’s experiences).

The third task that white allies must attend to involves making active efforts to avoid reactivity or engaging in acts of relational retaliation. Consistent with DiAngelo’s (2011) contributions about white fragility, Hardy (2016) noted that when encountering intense feelings during conversations about race, white people may respond by shutting down (retrenchment), arguing about who is right (rebuttal), or retaliating by lashing out (e.g., claiming that one is being personally attacked or accused of being ‘racist’). Tactic #3, “develop thick skin,” requires that white people be actively aware of and soothe any personal triggers, while also remaining focused on the experience of the person of color (p. 132). Of note is that the skill of self-soothing and managing strong feelings while also remaining engaged with others is similar to the skill of empathic attunement and presence practiced in psychotherapy. White clinicians may benefit by examining how they can use elements of their therapeutic skills in their development as antiracist allies.

The fourth task builds on several of the prior tasks, in that white allies must be aware of their own positions of privilege and reactions to racial stress. In this regard, Hardy (2016) noted that another common reaction to racial stress is offering advice. Offering advice (e.g., “You may be less triggered if you ignored those hurtful statements’) can be devaluing while also giving the impression that white people are more knowledgeable about the needs of people of color than they themselves are. Tactic #4 invites white allies to replace advice-giving with instead offering vulnerable disclosures about their own experiences (after attending to and making space for the experiences of people of color).

The fifth and final task of the privileged party is to avoid taking the ‘expert’ position. As Hardy (2016) described, the “KNOE” position involves taking a stance of someone who is knowledgeable, neutral, objective, and/or expert. Because whites are in a position of racial privilege, often what they say is considered both more knowledgeable, but also “free of the influence of race” (p. 132). As a result, whites are able to both accuse people of color from over-focusing on race while also not acknowledging how whiteness influences their beliefs and actions. Tactic #5, locating one’s own racial self in the conversation, invites white people to acknowledge and unearth how whiteness impacts their beliefs and behaviors. By being more aware of how race plays a role in their own lives, white people can be both more accountable and engaged in conversations about race.

In conclusion, one theme uniting the tasks and tactics recommended by Hardy (2016) is that white people must increase their understanding of how white privilege, supremacy, and fragility affect their interactions with others (both other white people, and people of color). By becoming more aware of what it means to be white, white allies may also be more able to explore and regulate feelings and behaviors that have the potential to cause further disconnection and harm. Addressing, being accountable for, and repairing relationship ruptures caused by enactments of white fragility also can serve to strengthen an actively antiracist white identity.

References

DiAngelo, R. (2011). White fragility. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3(3), 54-70. http://static1.squarespace.com/static/52f2de40e4b0cad7da8d9940/t/555752a2e4b0c9f331938206/1431786146884/wwsReading_week2.pdf

Hardy, K. V. (2016). Anti-racist approaches for shaping theoretical and practice paradigms.

In A. Carten, A. Siskind, & M. Pender Greene (Eds.),

Anti-racist strategies for the health and human services (pp. 125-139). Oxford University Press.

September 2020

The first Diversity Committee meeting for the new administrative year will be on September 21 (6-7:30pm) via Zoom. Any OPA members interested in joining the committee are welcome to contact Jess Binkley for more information.

The DC would also like to remind members of the list of social justice resources recently compiled by the OPA Board of Directors (see below for original list).

Resources

Local:

Don't Shoot PDX: Don't Shoot Portland is Black-led and community driven. Founded in 2014 by Teressa Raiford, we are a direct community action plan that advocates for accountability to create social change.

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Oregon: The American Civil Liberties Union of Oregon (ACLU of Oregon) is an advocacy organization dedicated to defending and advancing civil liberties and civil rights through work in the courts, in the legislature, and in communities. We fight for free speech, racial justice, criminal justice reform, religious liberty, reproductive rights, LGBT rights, immigrants' rights, and more.

Rosehip Medic Collective: The Rosehip Medic Collective is a group of volunteer Street Medics and health care activists active in Portland, Oregon. We provide first aid and emergency care at protests, direct actions, and other sites of resistance and struggle.

________________________________

National:

Racism, Bias, and Discrimination (APA): Individual racism is a personal belief in the superiority of one’s race over another. It is linked to racial prejudice and discriminatory behaviors, which can be an expression of implicit and explicit bias. Institutionalized racism is a system of assigning value and allocating opportunity based on skin color.

Multicultural Training Resources: Ethnic Minority Affairs Office (APA): Multicultural training resources covering topics such as indigenous peoples, immigration, racism, natural disasters, education, history of ethnic minorities and APA divisional resources related to ethnic minority affairs.

Article: "Black, Indigenous, and People of Color Are Unpacking Their Invisible Knapsack" By Antoinette Kavanaugh

________________________________

Books:

From: https://www.apacolorado.org/article/self-educate-anti-racism

- Maya Angelou - I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

- Mehrsa Baradaran - The Color of Money

- James Baldwin - The Fire Next Time

- Ta-Nehisi Coates - Between the World and Me

- Brittney Cooper - Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower

- Angela Davis - Freedom is a Constant Struggle

- Ralph Ellison - Invisible Man

- Frantz Fanon - Black Skin, White Masks

- Ibram X Kendi - How To Be an Antiracist

- Ibram X Kendi - Stamped from the Beginning (YA version: Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You)

- Bakari Kitwana - Why White Kids Love Hip-Hop

- Audre Lorde - Sister Outsider

- Toni Morrison - The Bluest Eye

- Toni Morrisson - Beloved

- Safiya Noble - Algorithms of Oppression

- Ijeoma Oluo - So You Want to Talk About Race

- Claudia Rankine - Citizen: An American Lyric

- Dorothy Roberts - Killing the Black Body

- Richard Rothstein - The Color of Law

- Bryan Stevenson - Just Mercy

- Malcom X - Autobiography of Malcom X

- Isabel Wilkerson - The Warmth of Other Suns

- Ellen D. Wu - The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Myth of the Model Minority

________________________________

Readings on Prison and Police Abolition

________________________________

Readings on Uprooting Whiteness

________________________________

Articles

________________________________

Policy/ Commission Reports

- Black Futures Lab - Black Census Project

- South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission - Here is a link to an international effort to enact systemic and institutional change. This commission provides valuable lessons for us to learn from. "While we have much work to do here, let us avail ourselves of work already done, learn and do better." Statement and resource from Michael Alter, Master of Public Affairs

________________________________

Movies / Videos

|